Fungus Among Us

Within every ecosystem on Earth, one ubiquitous form of life plays a central role in maintaining the health of all flora and fauna: fungi. These organisms partner in many ways with plant life to enhance the performance of the ecosystem. They break down organic debris, which enriches soils, and transport nutrients and water to plants through symbiotic relationships formed with roots, called mycorrizae. Fungi can also act as an information exchange system between plants, attracting beneficial fauna and conferring resistance to detrimental bacteria, viruses, and other fungi. Fungal life exists within a diverse spectrum of biological forms. These forms can be basically divided into three categories which all play different roles in the ecosystem: Saprophytes, Mycorrhizal fungi, and Endophytes.

Saprophytic mushrooms break down organic matter. Most gourmet and medicinal mushrooms are saprophytic. This breakdown process recycles carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and minerals, which are used by every component of an ecosystem. Oyster, Shiitake and Maitake belong to this group, preferring fresh organic material. Shaggy mane, Button mushrooms and Stropharia prefer to process more composted matter. Certain saprophytic mushrooms can be used in forestry to fight off blight. These work by out-competing fungi, such as Honey Mushrooms, which cause the roots of healthy trees to rot. Mushrooms viable for this purpose include Oyster, Garden Giant, Clustered Woodlover, Turkey Tail, Cauliflower Mushroom, and some Psilocybe species.

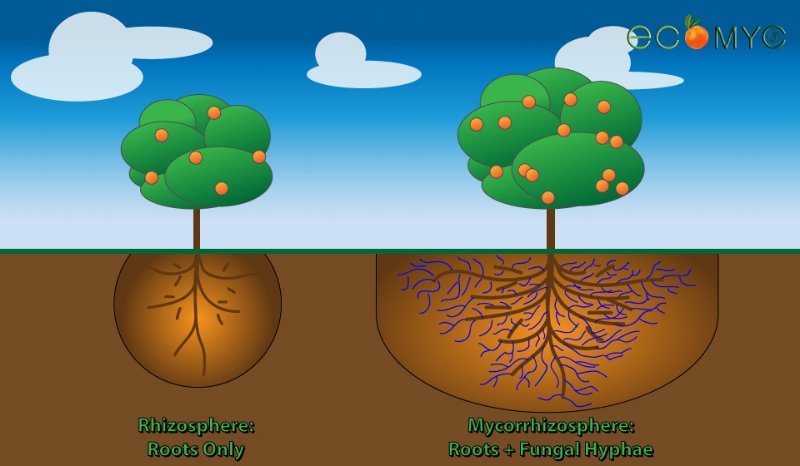

Mycorrhizal mushrooms grow in conjunction with plant roots. The mycorrhizal web allows plant roots to extend more than ten times further into the soil and thus increases water and nutrient uptake. In return, the mushroom gets sugars from the plant for its own growth. Multiple plants, even of different species, can be connected by the same web of mycelium and thus share nutrients and water among one another. This contributes to biodiversity in forests by allowing smaller understory plants to receive sugars for growth without the benefit of photosynthesis. In short, mycorrhizal fungi increase the resiliency and longevity of ecosystems. Some examples of these mushrooms include Matsutake, Boletus and Chantrelles.

Endophytic fungi form unique symbiotic relationships with plants. Their mycelium grows in between cell walls. This helps with nutrient absorption, fighting parasites, infections, predatory fauna and other fungi. Some species, such as the Curvularia, confer tolerances to extreme conditions such as drought. This could have far reaching implications including countering desertification and expanding oasis environments. One endophytic fungi, Piriformospora indica, has benefited wheat, corn, nicotine and parsley farmers because its presence promotes the growth of shoots and roots, increases seed germination rate dramatically and shields roots from pathogenic microbes. Endophytic fungi appear to be primarily benevolent organisms worth the effort to cultivate to face the many challenges of modern agriculture.

In the face of innumerable environmental crises, we need creative and effective solutions for problems like depleted soils, lack of biodiversity in flora and fauna, toxic accumulations in soil and groundwater, and total ecosystem collapse. Mushrooms are quickly becoming an essential component of these restoration efforts. Mycelial mats can be used to filter out microorganisms, silt, and pollutants from water sources in a process known as mycofiltration. No-till farming allows mycelium to grow undisturbed, therefore breaking down organic matter left over from harvest and increasing water retention and soil density while reducing the need for fertilizers. In many cases, poor soil can be rehabilitated using by adding organic matter, inoculating the soil with fungi that tend to form mycorrhizal relationships, and then planting the area.

A new branch of ecoforestry, mycoforestry, employs practices such as leaving woodchip debris in cut forests and inoculating them with saprophytic fungi. Other mycoforestry practices include using myceliated chainsaw oil for quick inoculation of cut trees and inoculating seedlings with mycelium prior to planting. In a process called mycoremediation, toxic accumulations in soils can be broken down and eliminated by laying mats of wood chips or straw inoculated with saprophytic fungi selected for their ability to break down specific toxins.

As a newly emerging science, fungi-based ecological projects present a wonderful opportunity for humans to learn and grow together with nature. Through cultivation and distribution of select mushroom species in our landscapes, local ecosystems will have a greater opportunity to thrive.

Increased biodiversity, richer soils, healthier and longer lived flora and fauna are beneficial to all and should be considered a goal for all aspiring gardeners and others working with nature. If you’ve enjoyed this and are interested in how fungi can play a greater role in your landscape, don’t hesitate to give Kaleidoscope a call or email!

Post by by Drew Arvidson, Kaleidoscope team member

All information sourced from Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World by Paul Stamets.